How to Catch Bluefish: Complete Guide to Techniques, Gear, and Locations

Species Profile

Quick Identification

Bluefish (scientific name Pomatomus saltatrix) are often simply called “bluefish” in the U.S., but regionally may be known as “tailor,” “snapper,” “baby blues,” “choppers,” or “elfs”.

They are easily recognized by their steel-blue or greenish back and bright silvery sides, with a deeply forked tail and very large mouth full of razor-like teeth.

Bluefish grow quickly; NOAA reports adults commonly reach 30–39 inches and up to 31 pounds in weight (the IGFA world-record is 31 lb 12 oz, caught in North Carolina in 1972). Smaller “snapper” blues of 7–15 inches are common when young.

Why Target This Species

Bluefish are prized by anglers both for sport and table fare. Their aggressive, schooling feeding makes them relatively easy to hook when present, but their high-energy fight and teeth make landing them challenging. They hit a wide range of baits and lures with lightning speed, so even beginners can often get strikes. However, their sharp teeth and sudden, powerful runs mean this is typically rated Intermediate/Advanced tackle (strong rods, heavy lines/leaders) for reliably landing big fish. As fighters, blues are famous: once hooked they unleash long powerful runs and aerial leaps that test angler skill and gear.

Culinarily, bluefish are edible but oily. They are sold fresh or smoked, but mature blues have a strong, “bloody” flavor. Most anglers prefer eating smaller fish (1–5 lb), whose flesh is milder. (If keeping blues for food, bleed them immediately and pack on ice to preserve quality; see Section 5.3.)

In the U.S., bluefish fishing peaks in summer through early fall. Along the Atlantic coast, the highest catches occur May–October when migrating schools move inshore. In general, waters in the 50–80°F range are best: blues spawn and feed in late spring/summer in northern waters, then migrate southward in fall and winter.

Behavior and Feeding

Hunting Pattern

Bluefish are pelagic pursuit predators that hunt in fast-moving schools. They often form large “wolf packs” of similarly-sized fish and herd baitfish toward the surface, then smash through the school in a feeding frenzy called a “bluefish blitz.” This blitz is extremely violent: the water churns with splashes and blood as dozens of large blues tear into menhaden, herring or other forage. Even a solo hooked blue is a sign that many more lie nearby. During a blitz, multiple rods often hook up at once.

Blues are most active in low-light periods, though they will feed whenever prey is abundant. They typically hunt at dawn and dusk; in long summer days, they often hold deeper by day and surface to feed as waters cool in the evening or morning. On calm overcast days they may even continue chasing bait through midday. In extreme cases (party-boat outings), anglers will chum fish and catch bluefish at any hour as schools remain in place.

Schooling vs. solitary: young bluefish almost always school tightly, but large adults (especially trophy “gator” blues) may roam in smaller groups or pairs, patrolling channels and edges of reefs.

Primary Diet

Bluefish are opportunistic carnivores and will eat almost any fish or squid they can swallow. Main prey are oily forage fish. In the Atlantic, this typically means menhaden (bunker), herring species (river herring, American shad, alewife), peanut bunker, and anchovies. They also feed on mackerel, weakfish, croaker, silversides, sand lance, Atlantic silverside and even smaller bluefish (juvenile blues are cannibalized by larger blues). Squid and small crabs may be eaten as well. In bay/estuary areas, blues will feed heavily on bay anchovies, white perch and juvenile striped bass.

Bluefish Diet & Feeding

Understanding the opportunistic carnivore of the Atlantic

🎯 Opportunistic Carnivores

🐠 Atlantic Coast Primary Prey

Seasonal Feeding Patterns

🌸 Spring & Early Summer: Young bluefish target small baitfish inshore including silversides, bay anchovies, and small menhaden.

☀️ Mid-Summer: Migrating schools gorge on massive rivers of bunker, creating feeding frenzies that anglers dream about.

🍂 Late Summer/Fall: Larger blues ambush dense schools of herring or peanut bunker before their southern migration, providing explosive action before winter.

Natural Baits

Artificial Lures

⚡ Feeding Behavior & Tactics

Visual Hunters: Bluefish feed primarily by sight on fast-moving prey, making flash and action critical in lure selection.

Greedy Feeders: Their voracious appetite means schools will stay around chopped fish chum or live bait strings, allowing multiple catches.

Wide Lure Range: The broad diet means virtually anything mimicking a fleeing baitfish or squid can trigger explosive strikes.

⚠️ Cannibalistic: Larger bluefish will readily eat smaller bluefish, so don't be surprised when a juvenile becomes bait!

Seasonal variation: Young bluefish in spring and early summer often target small baitfishes inshore (silversides, bay anchovies, small menhaden), while migrating schools in mid-summer can gorge on large rivers of bunker. In late summer/fall, bigger blues will ambush dense schools of herring or peanut bunker before heading south. This diet breadth means a wide range of baits and lures work: anything that mimics a fleeing baitfish or squid can trigger strikes.

Bait/lure selection: Because bluefish feed by sight on fast prey, anglers match this with flashy or erratic offerings. Natural baits should be oily and smelly – menhaden/sardine chunks, mackerel strips, squid pieces – rigged on wire- or monofilament leaders. Artificially, unweighted metal spoons and jigs that flash like fleeing fish are top producers (see Section 4.2). The greedy feeding habit also means chopped fish chum or a string of live bait can hold a school for multiple catches.

Where and When to Find Them

Key Habitat

Bluefish are coastal to nearshore fish that roam the continental shelf. Both juveniles and adults prefer shelf waters up to ~20 m (60 ft) deep. In the warm season they often concentrate near points, inlets, reefs, wrecks, and upwellings where baitfish gather. Young bluefish start life in shallow bays and estuaries (sandflats, marsh edges, tidal creeks) in spring, then gradually move offshore with age. By summer, schools range from beaches and sandbars out to the edge of the continental shelf. Key hotspots include ocean inlets, barrier beach surf zones, creek mouths, and offshore wrecks or rockpiles – anywhere that funnels bait or concentrates prey.

Along the U.S. Atlantic coast specifically: bluefish run from Maine to Florida (and into the Gulf of Mexico). In summer they are found north through New England and the Mid-Atlantic, while in winter the bulk of the population shifts south toward North Carolina and Florida. Remember the “school size rule”: most members of a given bluefish school are about the same size, so you will find clusters of 1–3 lb “snappers” in one patch and 10–15 lb “gators” in another. Fishing the right structure for the size class you seek is key.

Fishing Calendar

🐟 Bluefish Seasonal Migration Calendar

Atlantic Coast - Mid-Atlantic to New England

🌊 Migration Begins: First schools arrive offshore from the south, migrating north as waters warm. Blues move into inlets and surf within weeks after water hits ~60°F.

🔥 Peak Action: Schools common from Mid-Atlantic to New England. Fish retreat to deeper troughs during hot midday but feed heavily during early/late daylight.

📊 NOAA Data: 70% of annual recreational catch occurs in July–August

🎣 Party boats & surf anglers report blitzes almost daily in prime waters

🐊 "Gator Schools" Arrive: Feeding frenzy as schools prepare to migrate. Mid–late September often produces the largest fish of the year. Cooler water concentrates bait, making shore fishing (surf, jetties) extremely productive. Most blues depart by November.

🌊 Northern Waters: Rare north of Cape Hatteras. Only scattered large blues remain in deep offshore holes or off the Carolinas.

🌴 Florida: Bluefish present year-round in Florida waters.

🗺️ Regional Migration Pattern

Schools migrate northward following warming waters (~60°F trigger)

Mid-Atlantic to New England coastline filled with active schools

Largest "gator" blues arrive late, then migrate south by November

💡 Pro Tips

- Water Temperature: Watch for 60°F mark in spring – blues follow shortly after

- Time of Day: Summer midday can be slow; focus on dawn/dusk/night fishing

- Trophy Fish: Target mid-September through October for the biggest "gator" blues

- Shore Fishing: Fall produces best surf and jetty action as bait concentrates

- Winter Options: Head to Florida or target deep offshore holes in the Carolinas

Migration/Temperature: Bluefish migrate strictly by temperature – moving north with warming in spring and south when temps drop in fall. They generally avoid water below ~50°F. Therefore charting water temperature is crucial: look for the 50–55°F front and its relation to baitfish (e.g. menhaden) lines.

Optimal Conditions

- Tides: A falling tide (outgoing) is often best. TakeMeFishing advises that “the first couple of hours of a falling tide can signal great feeding opportunities” for blues, as bait tends to be drawn offshore. However, blues will bite on all tide stages if they’re present, so don’t ignore slack or flooding completely.

- Time of Day: Prime windows are usually early morning and late afternoon/dusk. In hot weather, midday fishing often slows as blues go deep. The “golden hour” before dark can trigger final blitzes. On cloudy or choppy days, however, blues may stay aggressive through midday. They have excellent vision and respond well to bright, erratic lures in low light.

- Weather: Coastal weather can matter less for bluefish than for other species, since these predators will eat in nearly any conditions if schools are present. However, bright sunshine can sometimes make them wary of shallow structure; overcast skies often improve topwater action. A steady, moderate chop (1–3 ft waves) tends to help conceal the angler’s presence and encourage active feeding.

Gear and Techniques

Recommended Setup

Primary Gear (Boat or Pier): A medium-heavy spinning or conventional outfit is ideal. For example, a 7′–8′ medium-heavy saltwater rod paired with a 3000–4000 series spinning reel (or 20–30 size conventional reel) provides a balance of casting distance and power. Spool 30–50 lb braided line as a main line for low stretch and high capacity, plus a 40–60 lb monofilament or fluorocarbon leader. Wire leaders are essentially mandatory to prevent bluefish from biting through. Use a 30–50 lb test wire or heavy mono leader (20″–30″ long) with a good snap or sleeve–swivel connection. Leaders of 10–15 feet are common when trolling deep or chumming.

Alternative Setup (Surf or Heavy Duty): For beach fishing, use a longer surf rod (9–11′) with heavy tip and butt sections for launching big lures. A high-capacity reel with 30–50 lb braid and at least a 60 lb leader/wire is recommended to handle large gator blues and abrasive conditions. In big surf, a surfcasting outfit with 12–20 oz sinker capacity may be needed for extreme conditions. Some offshore trollers use 50–80 lb tackle with live bait rigs when chasing trophy blues in boats.

Tackle Specs:

- Rod: Medium-heavy (20–50 lb line rating), fast or extra-fast action. Spinning or overhead (if trolling). Surf rods are longer, boat rods around 7–9 ft.

- Reel: Saltwater-rated reel with smooth drag; 3000–4000 (spinning) or conventional equivalent is standard. Drag should be able to hold 15–20 lb but easily adjusted for lighter line.

- Line: Braided main line (20–50 lb) or sturdy monofilament (30–50 lb).

- Leader: 40–60 lb mono or wire (stainless steel or coated). Wire is critical for large blues. Use barrel swivels and crimps or heavy-duty snaps to secure.

Effective Baits and Lures

Top 3 Natural Baits:

- Menhaden/Bunker (Whole or Cut): A classic bluefish bait. Rig small to medium bunker (2–6″) on a float rig or Carolina rig. For example, impale a whole peanut bunker on a circle hook and slip it under a popping cork, or cut 2″ strips of Atlantic menhaden on a bottom rig with a 3–4 oz egg sinker above. The oil and scent spread attracts blues.

- Mackerel Fillet or Chunk: Spanish mackerel (or Atlantic mackerel) fillets work well. Hook a strip through the snout or a chunk on a 4/0–6/0 hook on a high/low or dropper loop rig. Cast or drift this under a split-shot sinker. Mackerel’s lively smell and flash are irresistible to hungry blues.

- Squid Strips or Head: Tough squid is another top bait. Thread strips onto a #3/0–5/0 circle hook (through the mantle) or use a whole jumbo squid on a pulley rig. The texture and scent hold up in a bluefish’s mouth, unlike softer baits.

Rigging Tips: Always use wire or heavy mono leaders with bait to prevent bite-offs. Slide sinkers are recommended so blues can strip bait without feeling too much resistance (or use a fish-finder rig with a swivel). Keeping live or cut bait moving (slow trolling or jiggling) also mimics fleeing prey.

Essential Lures (2–3 types): Bluefish readily strike shiny, fast-moving lures. The most effective include:

Metal Spoons/Jigs: Heavy spoons like KastMaster, Hopkins Magic Minnow, Diamond Jig, or Deadly Dick in silver or chrome are must-haves. These survive bluefish teeth and cast far. Vary retrieves from steady to erratic jerks; blues often smash spoons as they flash through a school. Use sizes roughly 2–6″ (30–120 g) depending on water depth and fish size.

Topwater Plugs: Poppers and pencil poppers are killer when blues are busting on the surface. Lures like the Cordell Super Spot/RedFin or vintage 5–7″ pencil plugs (white, red/white, or chartreuse) draw explosive strikes at dawn/dusk. Walk-the-dog or chug aggressively to trigger reaction strikes.

Bucktail or Rubber Jigs: Large bucktail jigs (4–6″) or rubber squid jigs (“hoochies”) in white, blue, or translucent colors can work on a fast retrieve. Tipped with a strip of bait or soft plastic trailer, these are great for subsurface jigging. For example, rig a 3–5 oz bucktail jig on a 50–80 lb braid and swim it quickly through bait schools.

Recommended colors are predominantly silvers, whites, blues, and chartreuse – shades that mimic common baitfish. Bright contrasts (white/chartreuse) excel in murky water; tiger stripes or blues for clear water. Always hook lures with single inline hooks when possible. Bluefish quickly shred soft plastics and can cut treble hook tangles; swapping treble hooks for singles drastically reduces lost hooks and injuries.

Fishing Techniques

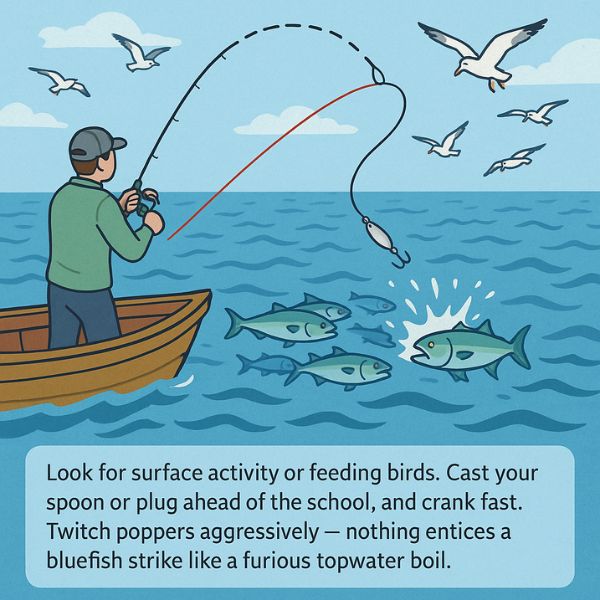

Casting and Retrieving: The bread-and-butter method. Look for surface activity or feeding birds, cast your spoon or plug ahead of the school, and crank fast. A sawtooth retrieve (burn, pause, jiggle, burn) often entices strikes. In general, fish your lure faster than you think: bluefish prefer a high-speed, erratic retrieve that mimics fleeing bait. Poppers should be twitched aggressively to splash and gouge water – nothing entices a bluefish strike like a furious topwater boil.

Float/Bait Rigging: For natural baits, many anglers use a popping cork rig or float rig to suspend a live/chunk bait (menhaden, clam, mullet) at a set depth. Cast toward birds or busting fish; allow bait to simmer and scent the area. Jerk the float occasionally to entice. Alternatively, free-line (no weight) a live peanut bunker under a balloon or with a sliding 1–2 oz sinker. This lets blues eat freely.

Trolling: Troll lures (deep-diving plugs or skirted jigs) through areas known to hold blues. Use a downrigger or heavy sinker to get baits down near the thermocline or structure in summer. Use 4–6 rod spreads with planers or weighed lures for covering water. Artificial squid jigs (hoochies) or slow-trolled plugs like the Roberts Ranger can work when reels are whirring through schools.

Chumming: When permitted, chumming with frozen menhaden or peanut bunker can create and hold a school. Use a wire basket or loosely scatter chunks upcurrent. Once blues lock on the chum slick, cast baits or lures into the frenzy.

Pro Tips: Bluefish are notorious for biting line and gear. Always check knots and crimps after each catch. Use long needle-nose pliers (with gloves) to unhook – never use bare hands near the mouth. After landing a fish, quickly change rigs or re-tie as teeth can fray leaders. When a school is working on the surface, keep your rod tip down and your drag snug; slack line only lets a hard-runner escape. If fishing jigs, vary the jigging motion – sometimes a simple lift-and-drop with pauses can trigger strikes in pressured conditions. Finally, be patient with size: if a school of medium blues is around and you want a “gator,” stay or chum them instead of instantly switching spots, as the biggest fish sometimes linger as others eat first.

Catch and Handling

During the Fight

Expect a bluefish to make long, powerful runs and sharp headshakes. Keep your drag set so the fish can pull line steadily; the goal is to tire the fish rather than knock it out cold. Maintain steady pressure and use the rod’s bending curve to absorb shocks if the fish leaps. Avoid turning the handle during a run – once the blue runs, hold the rod tight and let it spool line; re-engage reeling as it tires. One common mistake is to “jerk” too soon; instead, wait for tension before cranking.

When the fish nears the boat or beach, bluefish should generally be gaffed quickly rather than netted. Their hard teeth can rip nets, and bluefish thrash violently out of the water. The New York Sea Grant notes that large blues “are usually gaffed because a net will not stand up to the damage…Fish must be clubbed before the angler is able to retrieve the lure.” In practice, bring the fish close, use a solid gaff in the lower jaw or body, then immediately secure it (club or twist-kill) to prevent escape or injury.

Common mistakes: spooling too much line during runs, or trying to net a gator blue; both often lead to a lost fish or gear failure. Use heavy pliers or a hook knife to remove hooks once the fish is gaffed.

Catch and Release

If you plan to release blues, handle them with great care. They are very sturdy, but their stress levels rise quickly on the line. Whenever possible, use circle hooks to set deeply in the corner of the mouth (making unhooking easier). When bringing a blue aboard or alongside, keep it in the water as much as possible. If you must lift it out, support the belly and avoid grabbing the gills or eyes. Always keep your fingers away from the mouth area – bluefish can still snap violently out of the water.

Use a dehooking tool or long-nose pliers (preferably with heavy gloves) to remove hooks. Do not puncture vital organs. Minimize handling time and reviving: hold the fish in the water, mouth open into the current, until gills are moving and color returns, then release gently head-first. Studies show proper release (minimizing air exposure and internal injury) yields high survival for bluefish.

For Consumption

If keeping bluefish for eating, dispatch immediately and chill well. The easiest field method is to bleed the fish right after gaffing: quickly slice the gills or cut the carotid artery so the fish bleeds out, then store on ice. (Immersing the fish in a livewell or bucket of saltwater while bleeding will also improve flesh quality.) Once bled, do not let fresh water touch the meat – pack the fish dry on ice or in a cooler with crushed ice.

Bluefish flesh contains a strong bloodline (especially in larger fish), which tastes very “gamey” if not removed. Many anglers fillet the fish shortly after landing and then trim away the dark red lateral bloodline from each fillet before cooking. Smaller blues (under 5 lb) have less developed bloodlines and make excellent, mild-tasting fillets. Big bluefish have rich, oily white meat and are often preferred smoked, grilled whole, or in recipes that mask the intense flavor.

Culinary tip: Bluefish spoils quickly due to its oiliness, so prepare or freeze it as soon as possible. Proper bleeding and cold storage (and removing the bloodline) are the keys to keeping the meat firm and sweet. If well-treated, bluefish can rival other gamefish on the table.

Sources: Authoritative fisheries data and angler guides (NOAA, Sea Grant, fishing magazines) were used throughout to detail bluefish biology, behavior, and angling methods

as well as field tips from experienced anglers

takemefishing.org. All information is up-to-date through 2025 and relevant to U.S. Atlantic bluefish fishing. Each cited source is linked above.